Executive Summary

The “American Dream” has long included the opportunity to own your own home, which the Federal government incentivizes and partially subsidizes by offering a tax deduction for mortgage interest. To the extent that the taxpayer itemizes their deductions – for which the mortgage interest deduction itself often pushes them over the line to itemize – the mortgage interest is deductible as well.

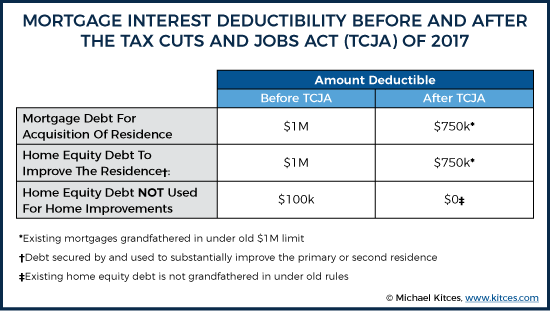

Since the Tax Reform Act of 1986, the mortgage deduction had a limit of only deducting the interest on the first $1,000,000 of debt principal that was used to acquire, build, or substantially improve the primary residence (and was secured by that residence). Interest on any additional mortgage debt, or debt proceeds that were used for any other purpose, was only deductible for the next $100,000 of debt principal (and not deductible at all for AMT purposes).

Under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, though, the debt limit on deductibility for acquisition indebtedness is reduced to just $750,000 (albeit grandfathered for existing mortgages under the old higher $1M limit), and interest on home equity indebtedness is no longer deductible at all starting in 2018.

Notably, though, the determination of what is “acquisition indebtedness” – which remains deductible in 2018 and beyond – is based not on how the loan is structured or what the bank (or mortgage servicer) calls it, but how the mortgage proceeds were actually used. To the extent they were used to acquire, build, or substantially improve the primary residence that secures the loan, it is acquisition indebtedness – even in the form of a HELOC or home equity loan. On the other hand, even a “traditional” 30-year mortgage may not be fully deductible interest if it is a cash-out refinance and the cashed out portion was used for other purposes.

Unfortunately, the existing Form 1098 reporting does not even track how much is acquisition indebtedness versus not – despite the fact that only acquisition mortgage debt is now deductible. Nonetheless, taxpayers are still responsible for determining how much is (and isn’t) deductible for tax purposes. Which means actually tracking (and keeping records of) how mortgage proceeds are/were used when the borrowisecong occurred, and how the remaining principal has been amortized with principal payments over time!

The Deductibility Of Home Mortgage Interest

The “current” form (before being recently changed by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, as discussed later) of the mortgage interest deduction under IRC Section 163(h)(3) has been around since the Tax Reform Act of 1986.

Under the rules established at the time, mortgage interest could be treated as deductible “Qualified Residence Interest” as long as it was interest paid on either “acquisition indebtedness” or “home equity indebtedness”.

Acquisition indebtedness was defined as mortgage debt used to acquire, build, or substantially improve the taxpayer’s primary residence (or a designed second residence), and secured by that residence. Home equity indebtedness was defined as mortgage debt secured by the primary or second residence and used for any other purpose. (And in either case, the property must actually be used as a residence, and not as investment or rental property.)

These distinctions of acquisition versus home equity indebtedness were important, because interest on up to $1M of acquisition debt principal was deductible (a combined limit for all debt on the primary and/or second residence), while home equity indebtedness interest was only deductible on the first $100,000 of debt principal. In addition, interest home equity indebtedness was not deductible at all for AMT purposes under IRC Section 56(b)(1)(C)(i), and Treasury Regulation 1.163-10T(c) limited the total amount of debt principal eligible for interest deductibility to no more than the adjusted purchase price of the residence (original cost basis, increased by the cost of any home improvements).

Example 1a. Bradley and Angela purchased their $700,000 residence by paying 20% down, and financing the rest with a traditional 30-year mortgage for $560,000. Because the $560,000 loan proceeds were used to acquire their primary residence, interest on the mortgage will be tax deductible.

Example 1b. Several years later, the residence has appreciated to $800,000, and the couple took out a $150,000 home equity line to repay some outstanding credit card debt, and finance the last two years of college for their children. Because the proceeds were not used to acquire, build, or substantially improve the primary residence, the $150,000 HELOC is treated as home equity indebtedness, which means only interest on the first $100,000 will be deductible (for regular tax purposes, and not be deductible for AMT purposes).

Notably, IRC Section 163(h)(3)(H)(i) also explicitly states that if acquisition indebtedness is refinanced, it remains acquisition indebtedness, to the extent of the original amount of acquisition indebtedness remaining.

Example 2. Continuing the prior example, if after several more years, Bradley and Angela have repaid their HELOC, and decide they want to refinance their original mortgage – which has now amortized down to a loan balance of $400,000 – they can retain acquisition indebtedness treatment on their refinanced mortgage. But only to the extent of the remaining $400,000 balance. Any additional debt – e.g., from a cash-out refinance – would not be acquisition indebtedness, even if it’s under the original $560,000 balance, because only the $400,000 remaining balance is considered acquisition indebtedness when refinancing (unless the additional funds are themselves used to substantially improve the residence).

Tax Treatment Of Mortgage Interest Is Based On Use Not Loan Terms

A key point in the tax treatment of mortgage interest is that whether or how much of the interest is deductible is determined by how the mortgage debt is used… and not necessarily by how the loan is structured.

As noted earlier, for mortgage debt to be treated as “acquisition indebtedness”, it must actually be used to acquire, build, or substantially improve that residence. (Where “substantial improvement” is based on whether the improvements are capital improvements that would add to cost basis, such as an expansion or permanent improvement, but not simply home maintenance and normal repairs.)

In the most common use case for a mortgage – a loan taken out to buy a house – the loan is clearly acquisition indebtedness, as the loan proceeds are literally used to acquire the primary residence.

Yet the reality is that because the determination of acquisition indebtedness is based on how the mortgage proceeds are used – not the structure of the loan itself – a home equity line of credit (HELOC) can also be acquisition indebtedness, if used to acquire, build, or substantially improve the residence!

Example 3. Jeremy has an existing but fully paid off primary residence worth $350,000. He decides to take out a $40,000 home equity line of credit, and draws on the HELOC, with a 5-year repayment period, to build an expansion to the house for his daughter and granddaughter to move in. Because the proceeds of the HELOC were used to make a substantial improvement to the primary residence (building an addition would increase the cost basis of the home), any interest on the HELOC will be treated as acquisition indebtedness, and not home equity indebtedness.

In addition, the fact that the determination of mortgage debt treatment is based on how the proceeds are used also means that there can be multiple loans that are each/all treated as acquisition indebtedness. This may be especially common in situations where buyers take out multiple loans all at once.

Example 4. Jenny is trying to qualify for a mortgage to buy her first residence, a $250,000 condo. To manage her exposure to Private Mortgage Insurance (PMI) given her limited downpayment, she takes out a $200,000 30-year primary mortgage (with no PMI), a $25,000 15-year second mortgage (with PMI), and makes a 10% ($25,000) cash downpayment at closing. Even though there are multiple loans, of which the first is a 30-year and the second is only a 15-year mortgage, because all of them were used to acquire the residence, interest on all of them will be treated as acquisition indebtedness.

In fact, there isn’t even a requirement that a mortgage loan be made by a traditional bank in order for it to be treated as acquisition indebtedness. It simply must be a loan, for which the proceeds were used to acquire (or build, or substantially improve) the primary residence, and it must be secured by that residence. Accordingly, even the interest payments on an intra-family loan can qualify for acquisition indebtedness treatment for the (family) borrower!

Example 5. Harry and Sally are hoping to purchase their first home to start a family, but unfortunately Harry has poor credit after getting behind on his credits cards a few years ago, and the couple is having trouble even qualifying for a mortgage. Fortunately, though, Sally’s parents are willing to loan the couple $250,000 to purchase a townhouse (financing 100% of the purchase), with favorable (but permitted under tax law) family terms of just 3% on a 10-year interest-only balloon loan (which amounts to a monthly mortgage payment of just $625/month before property taxes and homeowner’s insurance). To protect the parents, though – and to ensure deductibility of the interest – the intra-family loan is properly recorded as a lien against the property with the county. As a result, the $625/month of interest payments will be deductible as mortgage interest, because the loan is formally secured by the residence that the proceeds were used to purchase.

On the other hand, while a wide range of mortgages – including both traditional 15- and 30-year mortgages, intra-family interest-only balloon loans, and even HELOCs used to build an addition – can qualify as acquisition indebtedness when the proceeds are used to acquire, build, or substantially improve the primary residence, it’s also possible for traditional mortgage loans to be treated as at least partially as home-equity indebtedness and not acquisition indebtedness.

Example 6. John and Jenna have been living in their primary residence for 7 years. The property was originally purchased for $450,000, which was paid with $90,000 down and a $360,000 30-year mortgage at 5.25%. Now, a little over 7 years later, the loan balance is down to about $315,000, and the couple decides to refinance at a current rate of 4%. In fact, they decide to refinance their loan back to the original $360,000 amount, and use the $45,000 cash-out refinance to purchase a new car. In this case, while the remaining $315,000 of original acquisition indebtedness will retain its treatment, interest on the last $45,000 of debt (the cash-out portion of the refinance) will be treated as home equity indebtedness, because the proceeds were not used to acquire, build, or substantially improve the primary residence.

In other words, to the extent that the proceeds of a mortgage loan (or refinance) are split towards different uses, even a single loan may end out being a combination of acquisition and home equity indebtedness, based on exactly how the proceeds were used!

And the distinction applies equally to reverse mortgages as well. In the case of a reverse mortgage, often interest payments aren’t deductible annually – because the loan interest simply accrues against the balance and may not actually be paid annually in the first place – but to the extent that interest is paid on the reverse mortgage (now, or at full repayment when the property is sold), the underlying character of how the debt was used still matters. Once again, to the extent the loan proceeds are used to acquire, build, or substantially improve the residence, the (reverse) mortgage debt is treated as acquisition indebtedness (and its interest is deductible as such), while (reverse) mortgage funds used for any other purpose are at best home equity indebtedness.

Example 7. Shirley is a 74-year-old retiree who lives on her own in a $270,000 home that has a $60,000 outstanding mortgage with a principal and interest payment of about $700/month. She decides to take out a reverse to refinance the existing $60,000 debt to eliminate her $700/month payment, and then begins to take an additional $300/month draw against the remaining line of credit to cover her household bills. The end result is that any interest paid on the first $60,000 of debt principal will be acquisition indebtedness (a refinance of the prior acquisition indebtedness), but any interest on the additions to the debt principal (at $300/month in loan payments) will be home equity indebtedness payments.

Deducting Mortgage Interest Under The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017

Ultimately, the significance of these distinctions between interest on acquisition indebtedness versus home equity indebtedness isn’t merely that they have different debt limits for deductibility and different AMT treatment. It’s that, under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, the acquisition indebtedness limits have been reduced, and home equity indebtedness will no longer be deductible at all anymore.

Specifically, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) reduces the debt principal limit on acquisition indebtedness from the prior $1M threshold, down to just $750,000 instead. Notably, though, the lower debt limitation only applies to new mortgages taken out after December 15th of 2017; any existing mortgages retain their deductibility of interest on the first $1M of debt principal. In addition, a refinance of such “grandfathered” mortgages will retain their $1M debt limit (but only to the extent of the then-remaining debt balance, and not any additional debt). Houses that were under a binding written contract by December 15th and closed by January 1st of 2018 are also eligible. And the $750k debt limit remains a total debt limit of the taxpayer, which means it is effectively a $750k for the combined acquisition indebtedness of a primary and designated second home.

On the other hand, the new TCJA rules entirely eliminate the ability to deduct interest on home equity indebtedness, effective in 2018. There are no grandfathering provisions for existing home equity debt.

Which means in practice, the distinction is no longer between acquisition indebtedness versus home equity indebtedness, per se, but simply whether mortgage debt qualifies as acquisition indebtedness at all or not. If it does – based on how the dollars are used – it is deductible interest (at least to the extent the individual itemizes deductions). If the dollars are used for any other purpose, the mortgage interest is no longer deductible. Though again, the determination is based not on how the loan is structured and characterized, but on how the loan proceeds are used, and specifically, whether they’re used to acquire, build, or substantially improve the primary or second residence. (Notably, the fact that acquisition indebtedness must be used to acquire, build, or substantially improve a residence, and the loan must be secured by "such" residence, means that borrowing against a primary home to acquire, build, or substantially improve a second residence is not treated as acquisition indebtedness!)

In practice, this means that for many taxpayers going forward, mortgage interest will be “partially deductible”. Whether it’s a primary (acquisition) mortgage that’s deductible but a HELOC that’s not, or a HELOC that is deductible but a portion of a cash-out refinance that isn’t, the delineation of whether or how much of the mortgage debt (and its associated interest) is acquisition indebtedness or not matters more than ever. Because in the past, the fact that up to $100,000 of debt principal could still qualify as home equity indebtedness meant mortgages that were at least “close” to being all acquisition debt were fully deductible when the acquisition and home equity indebtedness limits were combined. Now, however, mortgage interest is either deductible for acquisition indebtedness, or not deductible at all.

Further complicating the matter is the fact that IRS Form 1098, which reports the amount of mortgage interest paid each year, makes no distinction between whether or how much of the mortgage principal (and associated interest) is deductible acquisition indebtedness or not. This isn’t entirely surprising, given that the mortgage lender (or the mortgage servicer) wouldn’t necessarily know how the mortgage proceeds were subsequently spent. Nonetheless, the fact that mortgage servicers will routinely report the full amount of mortgage interest on Form 1098, when not all of that interest is necessarily deductible, will almost certainly create taxpayer confusion, and may even spur the IRS to update the form. Possibly by requiring mortgage lenders or servicers to actually ask (e.g., to require a signed affidavit at the time of closing) about how the funds are intended to be used, and then report the interest accordingly (based on whether the use really is for acquisition indebtedness or not).

Fortunately, guidance in IRS Publication 936 does at least provide mortgage interest calculator worksheets to determine how to apply principal repayments with so-called "mixed-use mortgages" (where a portion is acquisition indebtedness and a portion is not). Specifically, the rules stipulate that principal payments will be applied towards home equity

In addition, existing guidance from IRS Publication 936 is not entirely clear with respect to how debt balances are repaid in the case of so-called "mixed-use mortgages" (where a portion is acquisition indebtedness and a portion is not) as ongoing principal payments are made. The existing rules do provide mortgage interest calculator worksheets that - under the old rules - indicated repayments would apply towards home equity indebtedness first, and acquisition indebtedness second (which would have been the most favorable treatment of repaying the least-tax-favored debt first). However, IRS Publication 936 has not yet been updated now that the home equity indebtedness rules have been repealed, to indicate whether taxpayers can similarly apply all their debt principal payments towards the non-deductible (formerly home equity indebtedness) balance first, while preserving the acquisition indebtedness (and its deductible interest payments) as long as possible.

Example 8. Last year Charles refinanced his existing $325,000 mortgage balance into a new $350,000 mortgage (on his $600,000 primary residence), and used the $25,000 proceeds of the cash-out refinance to repay some of his credit cards. Now, Charles has received an unexpected $25,000 windfall (a big bonus from his job), and decides to prepay $25,000 back into his mortgage. At this point, the mortgage is technically $325,000 of acquisition indebtedness and $25,000 of non-acquisition debt (for which interest is not deductible). But the mortgage servicer simply reports a total debt balance of $350,000. If Charles makes the $25,000 prepayment of principal, will the amount be applied against his $325,000 of acquisition indebtedness, his $25,000 of non-acquisition debt, or pro-rata against the entire loan balance? If the IRS follows the spirit of its prior guidance from IRS Publication 936, the $25,000 would be applied fully against the non-deductible (formerly home equity indebtedness) balance first, but at this point it remains unclear; similarly, even as Charles makes his roughly $1,800/month mortgage payment, it’s not clear whether the principal portion of each payment reduces his $325,000 acquisition debt, the other $25,000 of debt, or applies pro-rata to all of it!

Nonetheless, the fact that Form 1098 doesn’t delineate the amount of remaining acquisition indebtedness in particular, or whether or how much of the mortgage interest is deductible (or not) – ostensibly leaving it up to taxpayers to decide, and then track for themselves – doesn’t change the fact that only mortgage interest paid on acquisition indebtedness is deductible. Taxpayers are still expected to report their deductible payments properly, and risk paying additional taxes and penalties if caught misreporting in an audit. Though with a higher standard deduction – particularly for married couples – the higher threshold to even itemize deductions in the first place means mortgage interest deductibility may be a moot point for many in the future!

So what do you think? How will the changes to tax deductions for mortgage interest under TJCA impact your clients? How are you communicating about these changes with clients and prospects? Do these changes create any new tax planning opportunities? Please share your thoughts in the comments below!